Despite his success as a session musician, Hopkins struggled with his health throughout his life. His battle with Crohn’s disease and its complications took a toll on him physically and emotionally. However, his musical talent and passion never wavered. Hopkins continued to work with a wide range of artists, leaving an indelible mark on the music world.

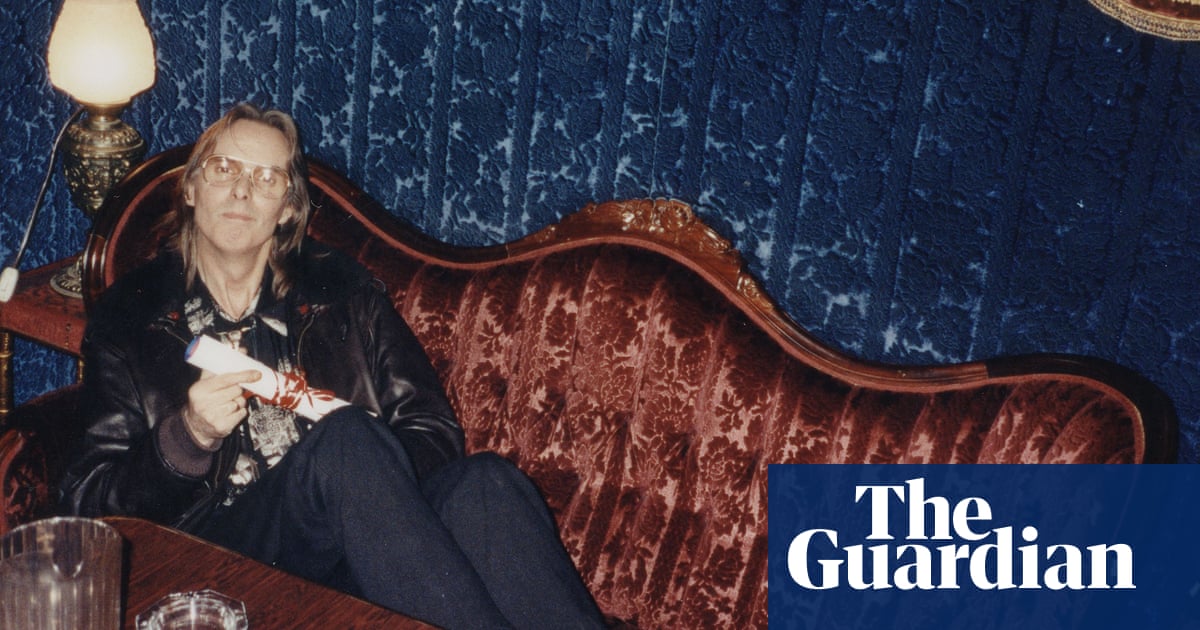

While Hopkins may not have received the recognition or financial compensation he deserved during his lifetime, his legacy lives on through the timeless music he helped create. The documentary The Session Man sheds light on his remarkable career and the impact he had on the music industry. Nicky Hopkins may have been a behind-the-scenes figure, but his piano playing truly stole the show in some of rock’s most iconic songs.

There is a remarkable section in the song where the band unexpectedly drops out, leaving Nicky to continue playing alone for several bars while maintaining the frantic tempo flawlessly,” Dawson explained. It’s no surprise that the Who wanted him to join the band, but he declined due to health reasons. Despite this, he was in high demand for other sessions not only because of his ability to come up with innovative variations on the spot, but also because of his technical expertise. Dawson recalled a time when Ritchie Blackmore, before his time with Deep Purple, mentioned that if a producer came in and said they were changing keys, the musicians would panic until they turned to Nicky, who could immediately transcribe it for them.

Another reason Nicky was sought after was his affability and lack of ego. “He would come into the studio and provide whatever the song needed, rather than demanding to be featured,” Dawson said. “He had a knack for finding these magical spaces between the guitars that really filled out the song.”

Talmy was so impressed by Hopkins’s work that he produced a solo album for him in 1966 titled The Revolutionary Piano Work of Nicky Hopkins. Hopkins began working with the Stones in 1967 for their album Their Satanic Majesties Request, and his contributions increased as Brian Jones’s drug addiction worsened. In the song “She’s a Rainbow,” his piano and harpsichord carried the entire melody. Two years later, the Stones’ track “Monkey Man” began with a mysterious piano trill that not only served as a memorable hook but also set the tone for the song’s haunting vibe. According to Treen, in an interview for a documentary, Keith Richards almost admitted that Nicky was responsible for many Stones songs, even though they were all credited to Jagger/Richards. When Dawson questioned Richards about this for his book, Richards simply shrugged and said, “Well, that’s the Stones for you.”

In 1968, Jimmy Page asked Hopkins to join Led Zeppelin, but he declined because he didn’t believe they would be successful at the time. Instead, he joined Jeff Beck’s group for a US tour, which had always fascinated him. His composition “Girl from Mill Valley” for Beck’s group showcased his compositional talent. After Beck’s group disbanded on tour, Hopkins remained in the US and became a prominent figure in the psychedelic scene on the west coast. He contributed intricate piano work to Jefferson Airplane’s Volunteers album and performed with them at Woodstock. He also co-wrote a song with the Steve Miller Band, “Baby’s House,” and joined Quicksilver, adding a dynamic piano element to their sound. A nine-minute piece he composed for Quicksilver in 1970, “Edward, the Mad Shirt Grinder,” became an FM radio staple with its lightning-fast piano runs and jazzy breaks.

“It’s amazing to think that Nicky not only played a crucial role in the innovative London music scene of the 60s but also left a mark on the west coast American scene,” remarked Peter Frampton, who met Hopkins while recording on George Harrison’s album All Things Must Pass in 1970.

Frampton later enlisted Hopkins to play on his solo album Something’s Happening in the early 70s. “Nicky played on two songs and turned them into piano songs,” Frampton recalled with a chuckle. “In both cases, he was the most captivating part of the song.”

Although Hopkins’s work remained exceptional, he struggled with drug and alcohol addiction in the 70s, partly to cope with his illness and partly due to the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle he experienced while touring with the Stones during their peak debauchery. “He was not cut out for that lifestyle like Keith was,” Dawson remarked. “He just didn’t have the resilience to handle it.”

During a tour with Joe Cocker, Hopkins was dismissed from the band for excessive drinking. “That’s quite an accomplishment in that company!” Dawson quipped.

While Hopkins eventually cleaned up his act, he remained fragile and required frequent hospitalizations. Although his prime working years had passed, he continued to secure lower-profile gigs and found success in Japan working on film soundtracks. The Stones later helped cover some of his mounting medical expenses, but a botched surgery ultimately led to his death. “Essentially, he died of a heart attack caused by the pain,” Treen explained. “The pain stemmed from gangrene in his stomach resulting from the surgery. Even if he had survived the heart attack, the extent of the gangrene was uncertain.”

Dawson believes that Hopkins still had more to offer despite his untimely passing. It saddens him and others to know that the pianist is now only remembered by die-hard rock fans of that era. “I can’t think of anyone else who played on as many iconic recordings and was such a key figure in the studio,” Dawson lamented. “Nicky may not have been the one in the spotlight on stage or the red carpet, but he was essential to everything.”

Hello! How can I assist you today?