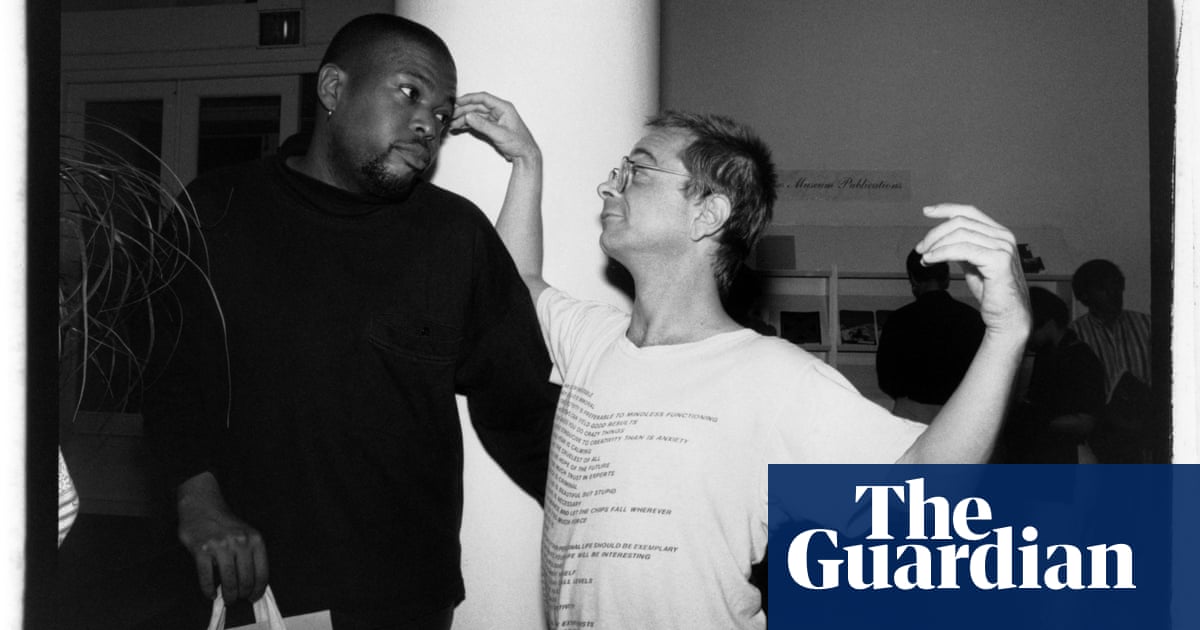

“An American writer.” This was Gary Indiana’s self-description when I first met him in the early 1980s at the Village Voice in the midst of the no-wave scene.

The Guardian’s journalism is independent. We will earn a commission if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

Small yet fierce, with a gaze that hinted at experience, Gary seemed like a genuine literary figure of downtown New York, drawing inspiration from Frank O’Hara’s personism and Lou Reed’s raw empathy. (I’d mention Joan Didion, but I’m certain Gary would haunt me for it.)

Originally born as Hoisington, Gary adopted the surname Indiana for reasons unknown. I interpreted this change as a subtle nod to Robert Indiana, fitting for a writer who served as the Voice’s art critic during the Reagan era.

Born in New Hampshire in 1950, Gary delved into the dark tales of Andrew Cunanan and the Menendez brothers, using their crimes as a critique of American society. He crafted a powerful play about Roy Cohn, produced sharp and sometimes campy videos, and established himself as a controversial figure in the art world and an icon of the underground scene.

Perhaps that’s why I felt compelled to assist him with a quintessentially New York predicament: preventing his landlord from evicting him from his East Village apartment. Drawing on my knowledge of local politics from editing top reporters, I presented Gary with various solutions. He must have resolved the issue, as he never mentioned it again. Owning an affordable apartment in a trendy neighborhood is one of New York’s great achievements, in my opinion.

Another hallmark of New York life is hearing the phrase “the check is in the mail.” To grasp the third accomplishment, delve into Gary’s fiction, where extravagant promises of pleasure often turn out to be falsehoods. One memorable example from his novel Horse Crazy involves the protagonist mistaking a man at a bar for the object of his desire, only to realize it’s a mere spot on the wall. Gary’s keen insight into the illusions of eroticism shines through in such instances.

I vividly recall editing an exceptional piece by Gary recounting his experience at a straight porn shoot in LA. While the article was rich in detail, its most striking aspect was the absence of eroticism, capturing the clinical detachment of professional pornography. We featured his piece on the cover with photos by Sylvia Plachy that perfectly complemented his perspective. Our publication of this candid piece, blending journalistic skill with literary flair, sparked controversy, with advertiser boycotts and bomb threats serving as reminders that the Voice was on the right track. Gary’s work embodied a unique blend of honesty and dissonance, challenging established power structures.

In an interview with Joy Press for the Voice in 2002, Gary reflected on his reputation for being brutally honest: “People thought I was needlessly cruel, but I was simply striving for honesty. It allowed me to inject a discordant note into the prevailing folly. Some view gestures against power as self-destructive, but if your sole concern is appeasing those in power, you might as well numb yourself with medication.” In a time when performative dissent often serves power dynamics, Gary Indiana’s words ring true.

Richard Goldstein, former executive editor of the Village Voice.

“